|

ALWAYS CATCH A STRAY THOUGHT |

|

WRITER charles roberts |

|

JUSTICE, LLC |

|

TOOLS FOR WRITERS |

|

Meet the Reader: SERIES

Created to analyze the mysterious target of our affections

– the reader - |

|

Meet the Reader: Sigmoid |

|

READER SIGMOID

Do not let the Greek letters bother you. I mention them because I was at a party and met another guest whose name was Socrates. It was not Halloween, he was not wearing his Pelast costume, and he appeared an average, slightly tipsy partyman.

Not sure how, perhaps like the original historical Socrates, we started talking about the atrociously short attention spans of the younger generation.

I put my hand on my knee and leaned forward towards Socrates.

“When I think, it’s like a country road in my old head, but the kids are running in the Indianapolis 500! They’re born into the pack - they don’t look back. When they start the race, they already know the track!”

I waved my hands together like a pair of checkered flags at a race finish.

“It always turns left!” I sat back shaking my head.

“Yeah” Socrates replied, without a blink. “And later in the race, it’s LEFT LEFT LEFT LEFT LEFT LEFT LEFT!”

We both roared, and spent the rest of the evening talking wildly like kids.

He liked my analogy. Liked it, adopted it, and RAN RAN RAN RAN RAN RAN.

Why did Socrates pick up on my joke and pass me a new one faster than a race car? Why did the other stodgy folks and the ‘swinging squares’ seem puzzled?

Maybe they didn’t get the joke, or the timing was off. Some people are just like that, we say.

Just like what? And exactly how many of ‘em are there?

Do you focus upon, then choose or discard thousands of actions each day, dear writer and reader?

And you readers with busy lives – are you still there, still reading? If so, WHY?

Pseudo-science could answer these questions, and no other sort would dare. Instead, we will seek to model these aspects of human behavior for further consideration. We will turn to math, and attempt to force meaning onto lines beyond the Greek symbols. You may always review your calculus later. We will leave derivations and data aside for this article.

During any moment of human experience, a personal discovery of some sort may generate a powerful response. Something has struck an emotional chord which draws our attention and drives our intellect. New or beautiful, useful or lovely, objects and events in our young lives create changes within us. This is often called ‘learning.’ Some of these events may be precious to our survival and prosperity, to our tribe, or for the survival of our world.

When kids get an average education, we know only a few will be left behind, and some will appear as geniuses. Most get the basic ideas presented - but how fast? For example, girls often pick up math more quickly; boys tend to learn physical skills first. Learning rates change with age, experience, interest, and duration of lesson. Some individuals seem to require special education, while others learn quickly and begin to innovate, ahead of the class.

Were they born smart? Perhaps an ‘old soul?’ They are willing to try new things first, can find the joy in flower-buds after a spring snow. When they try jumping off a cliff with the newest wings, others watch carefully - and then learn to fly. Those who followed the first might come to love flying, and soon thousands more will want to fly. How fast did the ‘joy of flying’ spread through the group?

Entertainers, traders, businessmen, politicians, commentators and artists of all kinds must perform their ‘storytelling’ - for whatever purpose - in such a way as to capture the child’s attention, impress them quickly, and then hold their interest until their goal is accomplished. The ‘story’ must achieve its goal, whatever the arena. Did you laugh, buy, invest, vote, believe, or love?

Did the child, adult, reader, or buyer tune out, leave, close their wallet, vote “no,’ or simply puke?

Salesmen, preachers, marketers, criminals, and con men rely on ‘staying ahead of the curve.’ They have studied their subjects, clients, or prey - scientifically and statistically - for a hundred years.

When considered as a bulk population, group behaviors are relatively predictable. Individuals may vary, be unpredictable, but any population of more than thirty-seven (believe it or not - thirty-seven) can be treated to all the advantages of statistics.

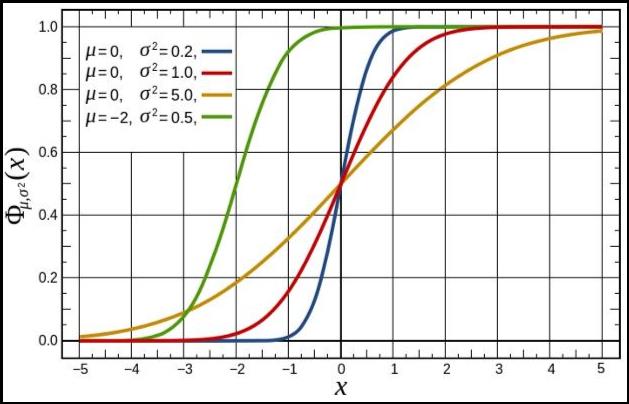

‘Sigma,’ a greek letter, a symbol, is used in statistics to show how much one group varies with respect to the average. In the same way, social scientists have created a model of learning - of personal discovery.

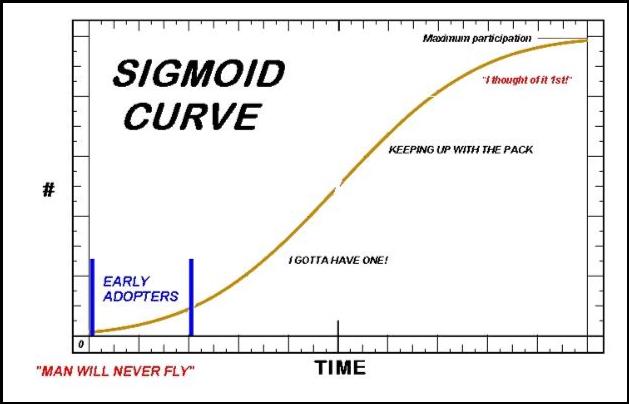

The sigmoid curve, S-shaped in general form, has been found useful in modeling how people react to change. The bulk of any population will react consistently to a new idea as it spreads through their general awareness. If the idea is of some value, more and more people will adopt it until it becomes mainstream, then perhaps declining and becoming passé over some defined time interval.

Here the general form is in gold, and if you refer back to the title graph, the sigmoid functions in red, blue, and green might apply to models of various different situations, such as product lifespan in a new market. (The full three dimensional calculus graphs are actually beautifully contoured surfaces.)

For our purposes, a hypothetical reader will be modeled. We shall turn our attention to the reader’s attention, so to speak, and correlate this over time with the sigmoid function.

How can we apply our scientific data about human behavior summarized by the sigmoid curve to literature?

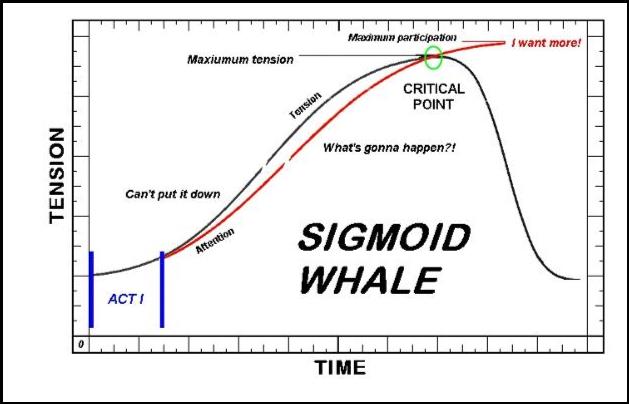

We will use the general sigmoid curve to represent the rising narrative tension in any work of literature. The reader will react to reading the story - this new experience - as an emotional moment of personal discovery.

We are mainly concerned with the voluntary reader who may stop reading without consequence – other than to the writer’s income. Professional readers, such as students and administrators, tend to be tied to their work, no matter how badly written.

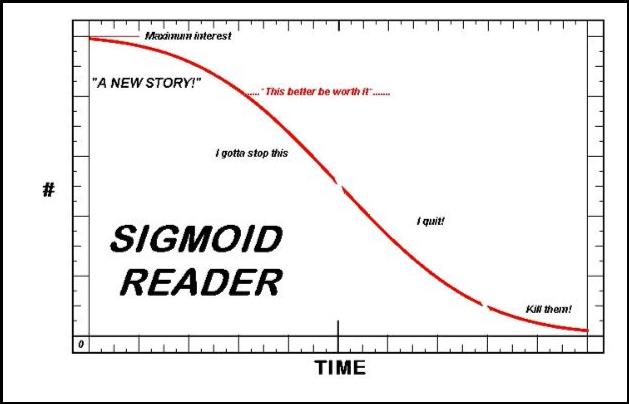

Human attention spans can be generalized by inverting the sigmoid curve. Children get tired after about half an hour. Adults will sit still and watch a ninety minute video drama. In that time period, any experience must be judged as worthwhile and exciting.

Every single experience, including reading, must eventually be interrupted by another. (Excepting of course, our final and mortal interruption….)

Have I wasted enough time? Are you sure the rest of this article will be worth it? If you are still reading, I presume to continue with this new idea.

Ancient Socrates the Greek failed to put pieces together. Some immediately saw brilliance, others just as quickly saw danger and disaster. How could he have gotten their attention and lectured them brilliantly before they exiled him?

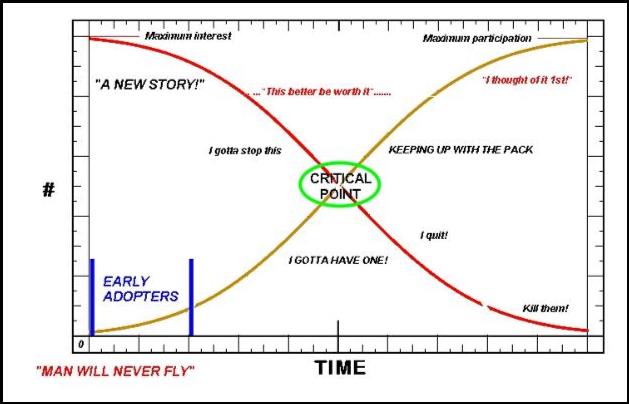

ANY kind of story can be analyzed and improved by combining the sigmoid curve of personal discovery and its inverse, the attention decay curve.

Upon the sigmoid curve of learning - of rising narrative tension - we can superimpose the Reader’s attention, the sigmoid reader curve - of attention decay.

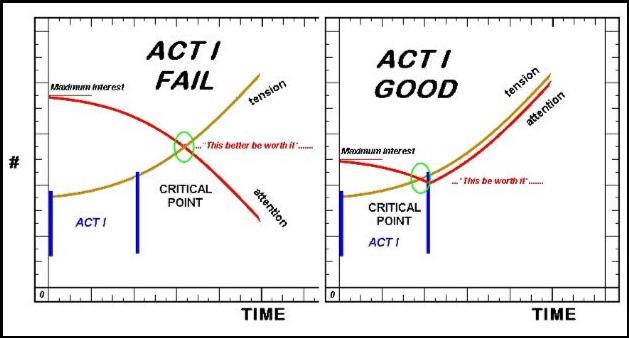

Where the two curves intersect is called the ‘critical point:’

If the reader isn’t on the tension curve early enough, you will lose them at the critical point. Will the Sigmoid reader be carried away by the sigmoid tension? Or will the reader’s attention continue to decay, conceivably to the point of bonfires?

Precisely: rising narrative tension must become magnetic before the reader’s margin of interest is exhausted.

“I knew that,” you say. “I invented it before you were born. It’s obvious.”

These two concepts are general models we can use in any specific situation we choose to define.

By examining the details of a particular case, whether a short story or an advertisement, a political campaign or a marketing blitz, we can adjust the critical point for maximum effect upon the largest numbers of the target audience. In non-fiction, facts and information must be presented promptly and be judged valuable. Perhaps the product sells better with a blue label, or a novel works better with a villain instead of a hero.

As a dramatic writer, capturing the reader’s attention must occur within ‘ACT 1.’

To be of use, however, we must match ACT 1 closely with the reader attention decay by focusing on details and adjusting each curve. We can’t change the interest of any particular reader, but we can choose our audience and manipulate the plot in order to produce a successful synchronization of the tension and the attention curves.

Apply this idea to chapter length. How long before Ms. Reader has to leave and pick up the kids? Hunger leads to dinner time. Sooner or later, nature calls. OR - Did she put your book down because she sailed past the critical point? Maybe the chapter dragged.

Are the reader sigmoid and tension sigmoid in synch for each chapter? How about for each paragraph? Every sentence?

Audience – has the writer picked the right model for his intended audience? A mature, experienced reader will give the story a longer margin of interest in the faith that the author knows his blades. The curve is stretched for that reader. They might finish the book no matter how bad.

A genre reader will drop the book if they don’t get their standard fare in ACT 1. His curve is steep, compressed, like a child’s. A broad reader will tolerate many types of experimental stories.

Narrative tension - does the selected tension sigmoid match the audience sigmoid model? A scientific paper had better have a steep ‘S,’ and make every bit of sense in the abstract. The scientist will read and cite the paper based on his impression from the abstract alone.

By combining differently shaped sigmoid curves, we can also model the ‘holy whale,’ which represents the general graph of ‘literary tension’ in a modern story:

The sequel might sell…

Constructing models of attention curves allows the writer to both to seduce the reader and create characters that act in believable ways.

By analyzing the interaction between attention span and plot tension, audiences can be selected and prose can be tailored to produce an attractive synchronization that will engage the reader and profit the writer. The writer can make changes based on real-world evidence like feedback and surveys.

When we analyze various types of readers’ attention spans and plot events, we can ‘out-write the reader’s expectations.’ Indeed, we may have ‘out-written ourselves,’ and an analysis of this sort will reveal unexpected insights to the author herself.

And if a story never generates a steep enough tension sigmoid, it will never garner much participation. The tension sigmoid is flattened vertically, or doesn’t exist.

If a person cannot or chooses not to read, it might be said their reader sigmoid begins below that of the tension sigmoid. There was never enough interest to begin - or their personality resembles an EKG flatline - as did the personality of ancient Socrates?

©CHARLES ROBERTS 2021 All images except title image originate with the author.

|